Suhandra Banerjee Banerjee

India

Distribution of E. coli phylogroups in healthy neonates reveals early gut resistome development

Suchandra Banerjee1, Amrita Bhattacharjee2, Rajlakshmi Viswanathan3, Mallika Lavania4, Sulagna Basu2

1.School of Biotechnology, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar 751024, Odisha, India.

2.Division of Bacteriology, ICMR-National Institute for Research in Bacterial Infections, P-33 CIT Road, Scheme XM, Beliaghata, Kolkata-700010, India.

3.Bacteriology Group, ICMR-National Institute of Virology, MCC Campus,130/1, Sus Road, Pashan, Pune- 411021, India.

4.Enteric Viruses Group, ICMR-National Institute of Virology, 20-A Dr. Ambedkar Road, Pune-411001, India.

Abstract

Background

Escherichia coli is an early-life colonizer of the human gut, often acquired within hours of birth. Based on the robust genomic plasticity shaped by horizontal gene transfer and ecological adaptation, E. coli is classified into eight phylogenetic lineages with distinct clinical implications. Plylogroups A and B1 are known to be gut commensals, whereas the other groups- B2, D, and F, harbor virulent determinants associated with extraintestinal infections. Despite well documented roles in disease, the distribution of E. coli phylogroups and their associated resistance profiles in healthy population remains poorly understood. The neonate gut microbiome represents an immunologically pristine niche where early colonization patterns profoundly influence lifelong health. Although maternal transmission is presumed to seed initial colonization, it remains unclear whether commensals persist or if pathogenic lineages with higher fitness outcompete them. Neonates are exposed to diverse microbial communities immediately after birth, including opportunistic pathogens from maternal or hospital environments, increasing colonization risk with drug resistant bacteria. Additionally, the gut serves as a reservoir for antimicrobial resistance determinants. This study characterized the E. coli phylogenetic distribution and antibacterial susceptibility patterns in healthy mother-neonate pairs to uncover early colonization trends and assess the burden of antimicrobial resistance in apparently healthy populations.

Methods

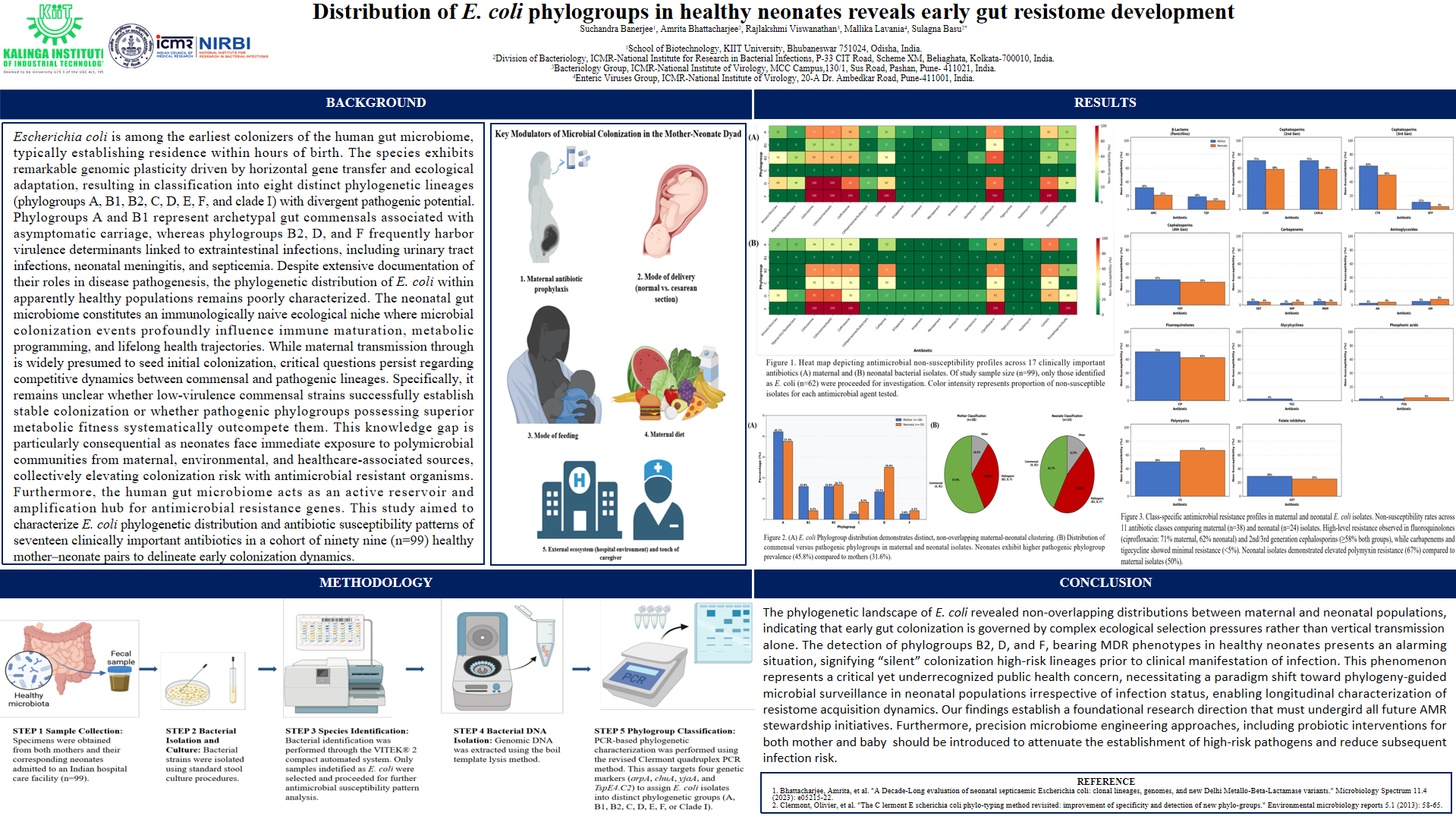

Stool specimens were collected from healthy mother-infant pairs admitted to a hospital. Bacterial strains were isolated following standard stool culture procedure. Identification and antibiotic susceptibility profiles for bacterial strains were carried out by biochemical tests and VITEK® 2 compact system. For all identified E. coli, PCR-based phylogroup detection was performed using the revised Clermont quadruplex PCR method, which targets the genes arpA, chuA, yjaA, and TspE4.C2.

Results

Among the identified E. coli strains (n=62), 38 were isolated from mothers and 24 from neonates. Phylogroup A was most abundant (42.1%) in maternal strains, followed by B1, B2 and D, each comprising 15.7%. Among neonates, phylogroup A was most frequent (37.5%), followed by D (29.1%), B2 (16.6%), and C (8.3%). Across both maternal and infant strains, resistant patterns were concentrated in B2, D, and F, with a trend of elevated resistance to β-lactam antibiotics and fluoroquinolones. Within neonates, B2, D, and F demonstrated the highest levels of resistance across β-lactams and fluoroquinolones. B2 and F exhibited 75–100% nonsusceptibility to these classes, while D showed variable resistance. Among maternal strains, phylogroups D and F were 100% nonsusceptible to third-generation cephalosporins. Notably, group A displayed moderate to high nonsusceptibility in both mothers and neonates. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was restricted to B2, D, and F in both maternal and neonate populations.

Conclusions

The phylogenetic landscape of E. coli revealed non-overlapping distributions between maternal and neonate strains, indicating that early gut colonization is governed by ecological pressures rather than just vertical transmission from mothers. Alarmingly, the presence of phylogroups B2, D, and F, marked by MDR traits in healthy neonates, signified the silent transmission of high-risk strains even before clinical manifestation of infection. These findings call for longitudinal studies utilizing phylogeny-driven microbial surveillance in neonatal populations regardless of infection status to characterize temporal dynamics of resistome acquisition. Furthermore, microbiome-targeted strategies like gut microbiome modulation through probiotics, should be evaluated to competitvely exclude pathogenic lineages and promote colonization by low-risk lineages during this critical developmental window.

Leave A Comment